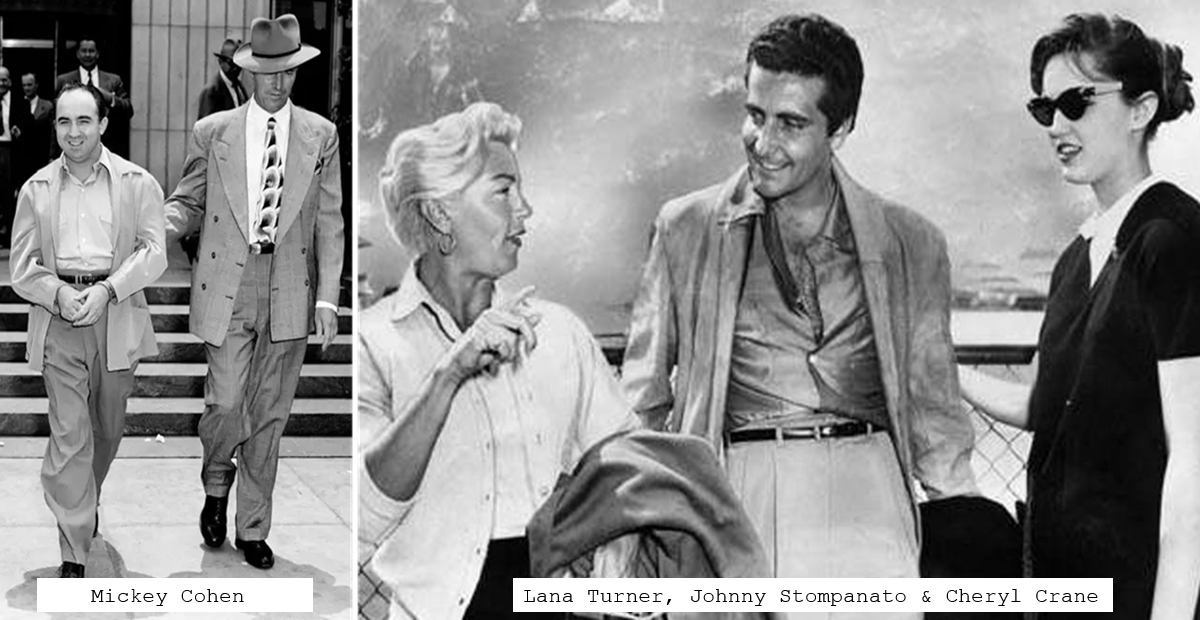

Mickey Cohen, ruthless head of the West Coast mob, didn’t react well when he learned that his tough-guy enforcer, Johnny Stompanato, had just been stabbed to death by a 14-year-old girl.

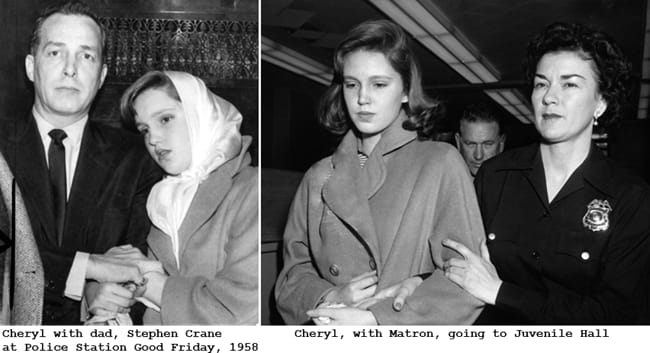

It was the evening of Good Friday, April 4, 1958. The teen was Cheryl Crane, daughter of iconic blonde screen actress, Lana Turner and restauranteur to the stars, Stephen Crane (Turner’s second of seven husbands).

Lana Turner was born Julia Jean Turner on Feb. 8, 1921 in Wallace, Idaho. Her mother was the 16-year-old daughter of a mine inspector and her father a 26-year-old miner.

Struggling financially, the family of three moved to San Francisco when Lana, then known as Judy Turner, was six. Four years later her father was bludgeoned to death near Potrero Hill after winning money in a traveling craps game.

Following her father’s murder, Lana’s mother worked 80 hours per week as a beautician to support them. In 1936 her mother was diagnosed with respiratory problems and, following her doctor’s recommendation, the two moved to Los Angeles.

When Turner was a junior at Hollywood High School, she skipped a typing class and was famously discovered while drinking a Coke at the Top Hat Malt Shop on Sunset Boulevard (not at Schwabs Pharmacy as has been commonly, and erroneously, reported).

Publisher of the Hollywood Reporter, William (Billy) Wilkerson, just happened to be in the malt shop at that time, was struck by Ms. Turner’s “beauty and physique” and asked if she would be interested in appearing in films. To which the 16-year-old replied, “I’ll have to ask my mother first”.

With mom’s approval soon secured, Wilkerson referred Turner to Zeppo Marx, who had become a successful talent agent after leaving his brothers’ famous act. Marx introduced the soon-to-be actress to prominent film director, Mervyn LeRoy, who secured for her a $50 per week contract with Warner Bros. ($1,120 in 2025) on Feb. 22, 1937.

Leroy and Warner Bros. agreed that Judy Turner, didn’t exactly sound like a movie star’s name. They convened a meeting to come up with something more glamorous. By the end of the meeting and not having come up with a name all could agree on, it was Turner who finally suggested the name, Lana. Approval was unanimous and Judy would live the rest of her life as Lana Turner.

Lana Turner's husbands, listed in chronological order, are:

Artie Shaw (band leader; married 1940, divorced 1940)

Steve Crane (restauranteur; married 1942, annulled; remarried and divorced 1943)

Bob Topping (millionaire sportsman; married 1948, divorced 1952)

Lex Barker (actor - Tarzan; married 1953, divorced 1957)

Fred May (rancher & May Dept. Store heir; married 1960, divorced 1962)

Robert Eaton (film producer & businessman; married 1965, divorced 1969)

Ronald Dante (Ronald Pellar) (night club hypnotist & con man; married 1969, divorced 1972).

Hollywood in the 1940s and 50’s was a much different place than it is now. Nearly all actors, and especially major stars like Lana Turner, worked under contract to one of the studios. In June of 1938 both LeRoy and his protege, Lana Turner, left Warner Bros. for MGM, with Lana’s salary increasing to $100 per week ($2290 in 2025).

1938-1939 was also when Lana became a fixture at Hollywood’s most star-studded nightclubs, like Ciro’s, The Mocambo and The Trocadero … when she was just 17-18 years old! These clubs were also the stalking grounds for the many Hollywood gossip columnists and press photographers who had dubbed Lana Hollywood’s Queen of the Night.

As her career progressed, both Turner and MGM became more and more obsessed about “the press”. This affected (infected ?) every aspect of her life. After she was cast as a high school teen in Love Finds Andy Hardy in 1938 - co-starring with her friend, Judy Garland (15) and Mickey Rooney (16) - Louis B. Mayer ordered that the 17-year-old’s cocktails and cigarettes be airbrushed out of nightclub photos.

Lana appeared in approximately 50 films during her 43-year career. Her most acclaimed films included the classic film noir, The Postman Always Rings Twice, with John Garfield (1946); The Bad and the Beautiful (1952); Imitation of Life (1959); Peyton Place (Best Actress nomination, 1957); Green Dolphin Street (1947).

By the time Cheryl was born, on July 25, 1943, Lana was just 23, had been in 18 films in the past 7 years and would divorce Steve Crane 27 days later.

Baby Cheryl (Lana called her “the baby” or “baby” until Cheryl was nearly 40) was raised as a typical Hollywood princess. Lana gave her caregivers strict instructions that she was never to be unattended. In fact, her nanny slept on a cot in her spacious bedroom. Lana even forbade Cheryl from playing with neighborhood children or having friends until her early adolescence. She never even rode a bus until she was 14. Cheryl compensated by creating imaginary playmates.

Lana’s concerns were clearly 1) her career, 2) maintaining her glamorous image, 3) partying and vacationing with men, 4) her daughter. Cheryl was brought up in pampered and indulged isolation … in the care of nannies and her grandmother.

Lana’s fourth husband, Lex Barker, was famous for starring as Tarzan in five films in the early 1950s after Johnny Weissmuller retired from the role. According to Cheryl’s superb 1988 autobiography, Detour: A Hollywood Story, Lex Barker crept into her room and raped her the first time when she was just ten. He told her it was his duty as a stepfather to educate her about the facts of life and that if she told anyone she would be sent to reform school and have to live on bread and water for many years.

Cheryl, naturally, felt alone and terrified. Finally, after three years of these secret assaults, she broke down and told her nanny and grandmother, Millie, while at her grandmother’s home. Gran, as Cheryl called her, immediately phoned Lana who rushed over from her home, leaving Lex asleep in their bed.

Even though the next day was Sunday, Lana was able to make arrangements for Cheryl to be examined by a doctor in the morning. She then returned home. Lex was sleeping. Lana quietly retrieved her pistol from her bedroom, then sat for hours, thinking, smoking and waiting for Lex to wake up.

Once he did, she confronted him with Cheryl’s accusations. He swore that Cheryl was lying, but Lana told him he had twenty minutes to collect his things and get out of her house, which he did.

The next day Cheryl experienced her first pelvic exam. After which the doctor told Lana that Cheryl showed signs of repeated, violent penetration for which she should have received stitches.

Lana refused to press charges over her fear of the negative press that would result. Stars of Lana’s magnitude also wanted nothing to do with psychiatric care, so young Cheryl never even received counseling or therapy. Just put it out of your mind was the advice she received from both parents.

Within a year, Lana had a new love, Johnny Stompanato, bagman and enforcer for west coast mob boss, Mickey Cohen. John was able to pass for respectable as the owner of The Myrtlewood Gift Shop, near UCLA in Westwood Village. The shop sold inexpensive pottery and wood carvings, passing them off as fine art … perfect for money laundering.

That Good Friday, Johnny was still enraged at Lana because she did not allow him to escort her to the Academy Awards ceremony nine days earlier. She had taken Cheryl and her mother instead. He was probably also still upset about being disarmed and thrown off the set of Lana’s film, Another Time, Another Place, in England by Sean Connery, after Stompanato had flown there from LA in a jealous rage and stormed the set. That night he assaulted Lana, choking her severely enough that her make-up man noticed the bruises the next day and called Scotland Yard who had him deported back to the States.

During their nightly arguments, Cheryl could hear Johnny vowing to Lana that if she tried to get rid of him he would either cut up her face himself or have it done, so that no one would ever look at her again.

On Good Friday night, Cheryl, hearing those shouted threats again from behind her mother’s closed bedroom door, could only think to go down to the kitchen and return with a large butcher knife she found on the counter. Maybe she could scare Johnny into calming down and/or leaving.

The 14-year-old opened her mother’s door holding the knife in both hands in front of her. Lana was just inside the bedroom with Johnny quickly coming up on her from behind. Lana, seeing Cheryl in front of her, stepped to the side (she claimed in testimony that she never saw the knife in Cheryl’s hands). Johnny kept advancing with one hand raised above him and, according to Cheryl’s testimony, walked right into the knife as she held it out in front of her. Lana would later testify at the police station that Johnny actually was holding some of his clothes on a hanger over his shoulder. Cheryl, not able to see the clothes, thought that Stompanato’s hand was raised to strike her mother (as he had done in the past).

The coroner’s report stated that the knife entered his abdomen, penetrated his liver and portal vein, cut a kidney, struck a vertebra, and twisted upward to puncture the aorta, making it a lethal wound causing rapid internal bleeding and death.

Among the police and ambulance personnel who descended on the home was Beverly Hills Chief of Police, Clinton B. Anderson, who was also a family friend. He briefly questioned Lana and Cheryl at the scene before all departed for the nearby Beverly Hills Police Station for more questioning, with Cheryl and her dad in the back of a police cruiser.

Due to accusations by the press, and soon by Mickey Cohen, that Cheryl and Lana would be shown favoritism by the local police, the chief, after more questioning, ordered that Cheryl be held on suspicion of murder and jailed. At that, Lana broke down and sobbed that her baby needed to come home with her.

If convicted as a juvenile, Cheryl faced life in prison. If convicted as an adult she could get the gas chamber.

Lana’s high-powered Hollywood lawyer, Gerry Giesler, and her attending physician tried to shield the star from the throng of press and photographers as they led her downstairs to her waiting limo.

Not long after they left, the short, pudgy figure of Mickey Cohen tore up those stairs two-at-a-time, shouting, “Who done it? Who done it?” The still-gathered group of reporters told him that Cheryl had admitted to it. “I can’t understand it”, he said. “I thought she liked Johnny. The three of us used to go horseback riding.”

Cohen was told that his friend’s body had been taken to the morgue. After racing there, the gangster simply said, “That’s him”, when shown the body.

Cheryl was transferred to Juvenile Hall in the morning. She ended up spending three weeks there. In her Juvenile Court hearing on April 24, Judge Allen T. Lynch ruled that Cheryl would be a ward of the court until her eighteenth birthday. The court also ruled she should live with her grandmother (Gran), finding that neither her mother nor her father offered a suitable home. She was also assigned two probation officers to whom she was to report weekly.

The following fall, Cheryl began her sophomore year at yet another new school, Beverly Hills High. Fortunately, the school year passed without incident.

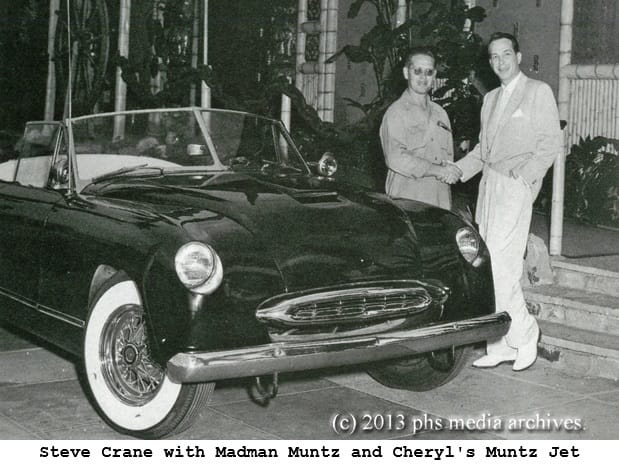

Cheryl’s next milestone would be her Sweet 16 birthday party on July 25, 1959. Her parents granted her wish for a dinner-dance for 40 couples at the Bel Aire Hotel. Steve Crane was the last to give Cheryl her gift: the gold key to a black Muntz Jet sports car, one of only 400 made by Madman Muntz’s car company. Her father had promised her any car she wanted but she insisted on the Muntz.

Unfortunately, the car was to provide too much freedom too soon for Cheryl. As she later admitted in her autobiography, her highly sheltered and privileged upbringing resulted in her inability to understand that actions led to reactions. “I still practiced a child’s ‘one-step’ thinking, not stopping to consider what might follow from taking that first step.” And “Freedom was heroin, and soon even too much was not enough”.

Cheryl also revealed in Detour that since around age six she knew she was more attracted to girls than to boys. She had disclosed this preference recently to her disapproving parents. Lana moaned that it was somehow her fault, and Steve became angry that the court-appointed psychiatrist had been unable to “cure” her.

Early in her junior year at Beverly Hills High, Cheryl reveled in cruising Sunset Strip with her girlfriends at night and hanging out at the new, hip coffee houses. She was still, however, a ward of the court with a 10 p.m. curfew.

She also had her first girlfriend, a high school classmate named Sally. Occasionally, Cheryl would drive to Sally’s parents’ big Beverly Hills home at night and sneak in through the window. It wasn’t long before Sally’s father discovered one of the girls’ sweet nothings notes and had Sally’s phone tapped. The recorded conversations confirmed his worst fears.

One day Cheryl was summoned from class to the guidance counselor’s office. Her probation officer was waiting and told her that Sally’s father had shown up at Gran’s front door with a shotgun. Cheryl was made to stay at the probation officer’s home for the weekend. By Monday, Sally had been transferred to a school in Arizona. Shortly thereafter, her parents moved away.

One of Cheryl and her friends’ favorite hangouts was Dolores’ Drive-In on Wilshire Blvd. All of the young, male car hops there were good looking and gay. Cheryl developed a close friendship with one of the car hops, an Adonis-like aspiring actor named Marty Gunn.

One night Marty told her that if she were to get married, that would make her a legal adult in California, and she wouldn’t have to wait until she was eighteen to be free of the court’s and her parents’ control over her.

“Are you sure?”, Cheryl asked.

“Sure”, Marty replied. “You wanna get married?”

Cheryl thought for a moment. “Sure, yes, I do.” She figured they could always get divorced after she turned eighteen.

“Great. Now we just need to get your parents’ permission”, Marty said. Cheryl knew that this would be a deal-breaker. Unless … she told them she was pregnant. But she quickly realized that her mother’s physician would disprove that soon enough.

Another possibility could be if Gran found them in bed together. A couple of nights later, Marty snuck in while Gran slept. They both tried to stay awake all night but fell asleep. The next morning, as expected, Gran was shocked and appalled to find them together. She phoned Lana and Steve and, as required by the court order, Cheryl’s probation officers.

Within a day, Cheryl and Marty visited Cheryl’s preferred P.O., Jim Discoe, to present their case. Soon, a Friday meeting was held with Cheryl, Lana, Steve and Gran in attendance, along with Jim Discoe and his colleague, Jeanette Muhlbach, but not Marty.

Surprisingly, there didn’t seem to be any objections to the wedding. Jim explained to Cheryl that they now only needed Judge Lynch’s blessing, which he told her he should have by Monday and would get back to her then.

On Monday, Jim didn’t call. Instead, he and Jeanette showed up at the front door looking very serious. Jim said he was sorry, but Judge Lynch felt she needed to be removed from the friends she associates with and placed in a school. The “school” was to be the El Retiro Reform School for Girls in the valley. Cheryl needed to pack quickly because her two P.O.’s would be driving her there.

Upon arriving, Cheryl saw that El Retiro was surrounded by a 10-foot-high wall, but once inside she decided it didn’t look bad. There was even an outdoor swimming pool and ballfields. Before long, though, her bad decision-making kicked in again and she and two other girls went over the wall and escaped. They were soon apprehended and returned to the school where their privileges were restricted.

Five weeks later, Cheryl again went over the wall with two different girls. As with the previous escape, all three were soon captured and returned.

Lana was becoming more concerned about what she saw as Cheryl’s deteriorating mental state, likely due to lingering effects of the Stompanato affair. She made the decision to send Cheryl to the Institute of Living, a private mental facility for wealthy patients in Hartford, Connecticut.

Early in her stay, Cheryl was confined in a padded cell because of her suicidal tendencies and emotional distress, which posed a risk of self-harm. She was heavily sedated and provided with psychiatric care.

Once her condition improved, she graduated to less restricted levels of care. Cheryl credited the encouragement and humor of fellow patient, Jonathan Winters, as helping her regain the will to live. Winters had recently suffered a nervous breakdown on stage at the Hungry I nightclub in San Francisco and later climbed into the rigging of the Balclutha sailing ship docked at Fisherman’s Wharf and refused to come down, shouting at police below.

Cheryl remained at the Institute until April 1962. She was finally a legal, free adult for the first time.

Cheryl settled in Los Angeles and began struggling with heavy drinking and sleeping pill use. After a suicide attempt, she was hospitalized again but then decided to turn her life around. She started working for her father as a hostess at his Polynesian restaurant, the Luau, on Rodeo Drive. This job helped her overcome shyness and gave her a new sense of purpose. She later studied restaurant and hospitality management for a year at Cornell University.

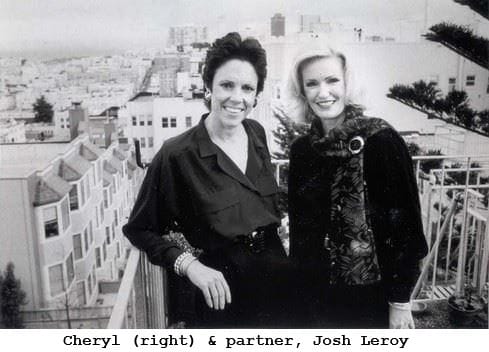

After publicly revealing her lesbian identity, she met model Joyce "Josh" LeRoy in 1968, with whom she formed a long-term partnership. By 1979, they moved to Hawaii, renovated houses, and prospered in real estate. Eventually, they returned to California, and Cheryl pursued a successful career in real estate while also writing memoirs and novels.

Source material: Detour: A Hollywood Story, by Cheryl Crane and Cliff Jahr, 1988, Wm Morrow & Co.