The killing of Billy Lyons by Lee “Stag” Shelton on Christmas night 1895 is a rare case where a single barroom homicide grew into one of the most enduring legends in American popular culture. It began as a brief, lethal quarrel in a St. Louis saloon and evolved into the endlessly reworked story of “Stagger Lee,” a mythic badman celebrated in hundreds of songs and stories.

A Christmas murder in Curtis’s Place

On the night of December 25, 1895, two Black working‑class St. Louisans crossed paths in a North Side saloon and set off a chain of events that would echo through American music for more than a century. William “Billy” Lyons, about 25, was a levee hand who lived on Morgan Street, close to the city’s bustling riverfront. Lee “Stag” Shelton, sometimes misreported as “Sheldon,” worked as a carriage driver and pimp and was known in local underworld circles.

According to the St. Louis Globe‑Democrat’s contemporary account, Lyons and Shelton were “friends” who had been drinking heavily and were in “exuberant spirits” when an argument over politics broke out in Bill Curtis’s saloon at the corner of Eleventh and Morgan. At some point, Lyons grabbed Shelton’s Stetson hat and refused to give it back; Shelton demanded its return, then drew a revolver and shot Lyons in the abdomen, calmly reclaimed his hat from the wounded man’s hand, and walked out.

Lyons later died of his wound, making the shooting one of several holiday murders recorded in St. Louis that Christmas, but hardly the bloodiest or most sensational by the raw numbers. Nevertheless, this particular killing stood out - perhaps because of the vivid detail of the hat, the racialized press fascination with Black vice districts, and Shelton’s own reputation - and it quickly began to take on a life beyond the courthouse.

St. Louis: a city primed for legend

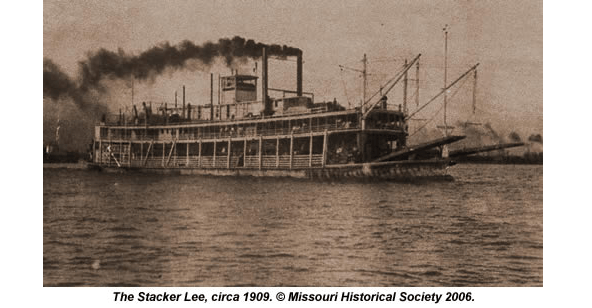

To understand why this mundane saloon killing resonated so strongly, it helps to look at the St. Louis of Shelton and Lyons’s day. In the late nineteenth century, St. Louis thrived as a Mississippi riverboat hub and rail junction, funneling gamblers, drifters, river workers, and itinerant railroad men through its levee and adjacent neighborhoods. The city’s Black population grew rapidly after the Civil War as formerly enslaved people moved north for factory work and relative freedom, swelling the urban working class and feeding the nightlife that clustered near the riverfront.

Vice districts like Chestnut Valley and the area around Morgan Street became famous for saloons, gambling joints, “nickel shot” bars, and brothels where Black and white patrons mixed more freely than in many other parts of the city. Law enforcement lagged behind this growth and was often corrupt, brutal, or indifferent, creating an atmosphere in which violence was common and often resolved informally or through patronage rather than strict legal process. In this environment, a quarrel over a hat and wounded pride could easily escalate into a shooting, and the story would then be retold in work camps, levee shanties, and barrooms with each narrator adding a little color.

Shelton’s own image fit comfortably into emerging “badman” folklore in Black communities - figures who defied white authority, carried weapons, and refused to back down from an insult. Even if the actual shooting was a grimly ordinary homicide, the idea of a man who would kill to reclaim his Stetson amid the crooked saloons and “chance emporiums” of St. Louis was tailor‑made for transformation into song.

From court case to folk hero

In the immediate aftermath, Shelton was arrested and charged with murder. Surviving records and later reconstructions suggest a contentious legal path: at least one jury hung over whether the killing was premeditated murder, manslaughter, or a kind of heated self‑defense. Eventually, Shelton was convicted and sent to prison; he was later paroled, ran into trouble again, and died in custody in 1912, a minor underworld figure by official records but already becoming a major character in oral tradition.

While the courts processed the case, workers and musicians along the river and rail lines took the story in their own direction. Work songs, field chants, and folktales about “Stack Lee” or “Stagolee” began to circulate in the years after the shooting, highlighting the defiance, the hat, and the sense that this was no ordinary man. By 1903, collectors had captured the earliest known written lyrics, and by 1923 the first commercial recordings - such as “Stack O’ Lee Blues” - had begun to codify the ballad on record.

In these versions, the facts of the 1895 case became malleable clay. The bar might be called the Bucket of Blood or the White Elephant; the city might shift to Memphis or New Orleans; the date might move decades forward into the twentieth century. Yet the core remained recognizable: a man named Stack or Stagger Lee kills a man named Billy Lyon/Lyons/Lion/DeLyon over a Stetson hat that’s been taken, lost, or “won” in a game. The song did not aim to preserve courtroom accuracy; it aimed to carve out a powerful archetype.

The many faces of Stagger Lee

Across the 200‑plus versions documented by historians, Stagger Lee’s character swings wildly between extremes. In some songs, he is a sadistic killer who shoots Billy without provocation, sometimes killing a bartender or other bystanders along the way. In others, he is a wronged man defending his honor after being cheated or insulted, a folk hero standing against unfairness in a rigged social order. The badman tradition allowed listeners to flirt with vicarious rebellion, even as real‑world violence remained dangerous and often punished.

These narrative variations reveal more about the communities that carried the song than about the historical Shelton himself. Versions that emphasize Stagger Lee’s cruelty and indifference to pleas for mercy underscore the bleakness of life on the margins, where appeals to law or morality seemed hollow. Versions that cast him as a kind of avenger - someone who insists on respect and refuses to bow to anyone - speak to a desire for agency in a society structured against Black working people.

As the ballad spread, it also absorbed elements from other legends and local tales, merging with broader “badman” lore like that surrounding figures such as John Henry or Railroad Bill. The details kept changing, but the name “Stagolee” or “Stagger Lee” remained a shorthand for uncompromising, violent masculinity rooted in specific Black American experiences at the turn of the century.

From blues standard to pop hit

By the 1920s and 1930s, “Stack O’Lee” had become a staple of the blues and jazz repertoire. Artists like Ma Rainey and other early recording stars shaped the story into a moody, swaggering standard, sometimes stretching or compressing verses to fit their own styles. The song’s flexible form made it ideal for improvisation, and its reputation grew with each new recording in the pre‑war era.

Over time, a remarkable roster of performers put their stamp on the tale. Duke Ellington, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, and James Brown all recorded versions that translated the ballad into big‑band swing, New Orleans R&B, rock and roll, and funk‑inflected soul. Wilson Pickett, Dr. John, The Clash, Bob Dylan, and Nick Cave each approached Stagger Lee through their own musical lenses, from gritty soul to punk and goth‑tinged storytelling. Even Elvis Presley tried it in a loose 1970 rehearsal that later surfaced on bootlegs, a sign of how deeply the song had penetrated mainstream awareness.

Each of these versions reshaped the myth. Some emphasized the groove and party atmosphere, turning the murder ballad into a dance‑floor favorite that only hinted at the blood in the lyrics. Others leaned into the darkness, magnifying Stagger Lee’s brutality or framing the story as a commentary on American violence, racism, or masculinity. The song’s adaptability kept it alive far beyond the folk and blues circuits where it began.

Lloyd Price and the chart-topping “Stagger Lee”

The most commercially famous rendition arrived in 1958–59, when New Orleans–born R&B singer Lloyd Price released “Stagger Lee,” a driving, horn‑driven arrangement that took the old narrative into the heart of rock‑and‑roll radio. Price’s version streamlined the story into a punchy pop structure while retaining the core elements: a barroom confrontation, a dispute over a hat, and the fatal shot that cements Stagger Lee’s fearsome reputation.

Lloyd Price - Stagger Lee

Price’s recording topped the Billboard pop chart in early 1959 and introduced the story to millions of listeners who knew nothing of Shelton, Lyons, or the St. Louis levee. For many, this became the definitive version, and its success ensured that “Stagger Lee” would be covered again and again in subsequent decades. The song’s presence on mainstream radio also sparked occasional controversy, as some program directors balked at airing a murder ballad with such unapologetic bravado, leading to tamer rewrites or alternate lyrics in certain settings.

Yet the power of the Price version lay precisely in its refusal to sanitize the badman. It presented Stagger Lee as a charismatic, dangerous figure whose transgression was also a kind of liberation from constraint, echoing the deeper folklore even as it packaged the story for a broad audience. From this point on, “Stagger Lee” was no longer just a folk song; it was a pop standard, a cinematic vignette, and an endlessly revisited narrative template.

Beyond music: comics, films, and cultural commentary

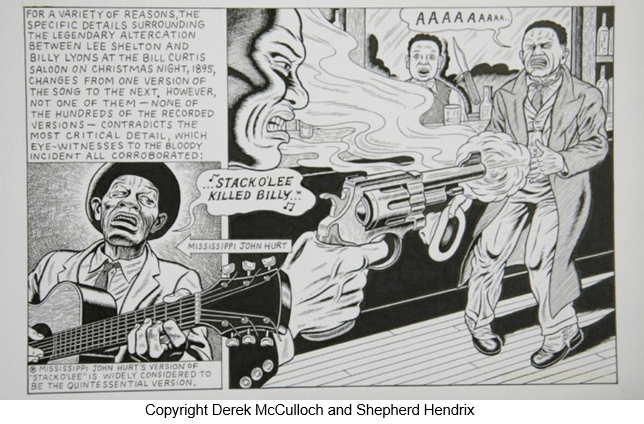

The twenty‑first century brought new media into Stagger Lee’s orbit. In 2006, writer Derek McCulloch and artist Shepherd Hendrix released a graphic novel retelling the story in detail, blending historical research with mythic framing to explore both the 1895 killing and its long afterlife in song. The book uses visual storytelling to inhabit St. Louis’s vice districts, the world of Black working men, and the shifting line between documented fact and folk memory.

Film and television have also drawn on the legend. Samuel L. Jackson performs a fierce version of “Stagger Lee” in the 2007 film Black Snake Moan, using the song as a vehicle for raw emotion and blues history. In John Sayles’ Honeydripper (2007), a performance of the song by Eric Bibb is woven into the narrative as a commentary on the action and on the evolution of Black Southern music. These appearances show how Stagger Lee serves not just as a character but as a cultural symbol, invoked whenever creators want to tap into the tension between law, violence, and self‑assertion.

Writers and scholars have continued to unpack the legend, analyzing how the ballad reflects attitudes toward crime, race, and masculinity from Reconstruction through the Civil Rights era and into the present. Some focus on the way the story erases Billy Lyons as a person, turning him into a mostly anonymous victim in service of Stagger Lee’s myth; others read the ballad as a critique of the conditions that produced such figures in the first place.

Fact, folklore, and the enduring appeal of Stag Lee

When the Globe‑Democrat reported Lyons’s murder in December 1895, it could not have anticipated that this “saloon of Bill Curtis, at Eleventh and Morgan streets” would become one of the most famous crime scenes in American music. To the newspaper, it was one of several holiday killings, notable but not unprecedented in a rough river city at the turn of the century. To the singers, storytellers, and listeners who picked up the tale, it became something more: a canvas on which to project anxieties and fantasies about power, respect, and survival.

The historical record of the case is relatively thin but clear: two men, both drinking, a political argument, an insult involving a hat, a gunshot, a death, an arrest, a prison term. What transformed that bare outline into an immortal story was the way communities used it - through work songs, blues, jazz, R&B, rock, punk, and beyond - to grapple with the realities of life under racism, poverty, and precarious work. Every time an artist changes the bar’s name, moves the city, or alters Stagger Lee’s motives, the song reveals more about its singer and audience than about Shelton himself.

Today, historians can stand at the modern equivalent of Eleventh and what is now Convention Plaza and know that somewhere near this intersection, on a cold Christmas night in 1895, Billy Lyons fell to the floor of Curtis’s saloon and Lee Shelton walked out with his Stetson. From that small, grim moment grew a towering legend - a reminder that in American culture, the line from police blotter to myth can be surprisingly short, especially when the story carries a beat people cannot stop singing.

Your Entire Studio, Right on Your Laptop

Record, edit, and publish your best content without needing a crew, studio, or complicated setup.

With Riverside, you capture high-quality video and audio, edit it instantly with AI, and turn one recording into clips, posts, and podcasts ready to share. All so you can spend less time troubleshooting tech and more time creating the content your audience actually wants.

Imagine finishing your session by lunch and sharing finished clips before your afternoon coffee. Riverside puts the power of a full studio right on your laptop so you can create faster, sound better, and look professional anywhere.