On Christmas Day 1929, in rural Stokes County, North Carolina, tobacco farmer Charles “Charlie” Lawson murdered his wife and six of his seven children before killing himself, turning what should have been a quiet holiday into one of the South’s most haunting true‑crime legends. Nearly a century later, the Lawson family murders remain a disturbing blend of established fact, local memory, and fiercely debated motive.

The Lawson family and their world

Charlie Lawson was a 43‑year‑old sharecropper and small tobacco farmer living near Germanton, a rural community north of Winston‑Salem. He and his wife, Fannie, married in 1911 and eventually had eight children; one son, William, died in 1920, leaving seven surviving children by late 1929.

By the late 1920s, the family - like many small farmers - struggled financially, but they were not destitute and were generally regarded as respectable, hard‑working people in their community. In 1927, Charlie managed to buy a modest farm rather than just tenant land, a step up that suggested some stability and ambition.

The children living at home in December 1929 were:

Marie (17)

Arthur (16)

Carrie (12)

Maybell (7)

James (4)

Raymond (2)

Mary Lou (about 4 months old)

Neighbors and later recollections describe Fannie as a devoted mother, the older children as dutiful and close to their siblings, and Charlie as strict but not widely viewed as violent before the murders. That image, however, has been challenged by later testimony and theories about what was happening inside the home.

The strange Christmas portrait

One of the most chilling details in the Lawson story is an outing just days before Christmas 1929. Shortly before the holiday, Charlie took Fannie and all the children into Winston‑Salem for new clothes and a formal studio photograph, something unusual for a poor farm family of that era.

The Lawsons chose hats, coats, and dresses, and then sat for a posed family portrait with everyone neatly dressed and composed. That photograph would become infamous after the murders, widely reprinted in newspapers, on postcards, and in later books as a “before” image of a doomed family.

Some researchers and relatives have argued that this elaborate outing, at a time when money was tight, suggests premeditation—that Charlie wanted to leave behind a last, idealized image of his family because he already planned to kill them. Others have suggested it might simply reflect a desire to mark Christmas or show pride in modest success, but in hindsight it sits uneasily beside what followed.

Christmas Day: the murders unfold

Christmas Day 1929 began, outwardly, as a normal holiday on the Lawson farm. Marie reportedly baked a two‑layer Christmas cake that morning, a detail that would later gain grim symbolism when the cake was displayed to paying curiosity‑seekers with one slice removed. Arthur, the 16‑year‑old son, had been sent to town on an errand - whether at his own initiative or at Charlie’s request has been disputed, but his absence would save his life.

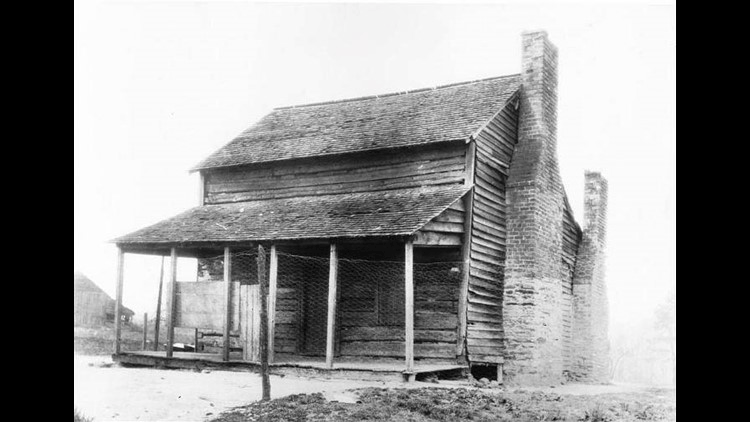

Lawson family home, Stokes County, North Carolina

Sometime in the early afternoon, Charlie set his plan in motion. According to reconstructions based on the scene and contemporary reports:

He first lay in wait near the tobacco barn for his daughters Carrie (12) and Maybell (7), who were walking along the path to visit their aunt and uncle.

As they came within range, he shot them with a 12‑gauge shotgun, then bludgeoned them to ensure they were dead, possibly to conceal the gunshot damage or simply to be certain.

He placed their bodies carefully inside the tobacco barn.

Charlie then returned to the house. Fannie was on the front porch when he approached. He shot her, killing her there at the doorway. Inside, the children heard the shot. Marie screamed; the two small boys, James and Raymond, tried to hide.

Charlie entered the house and:

Shot Marie, the eldest daughter, likely in a bedroom or main room of the house.

Searched for the two small boys and killed them - accounts vary as to whether he shot, bludgeoned, or both, but both were found dead in the home.

Finally, he killed the infant, Mary Lou, believed to have been either bludgeoned or suffocated - some accounts say she was killed by a blow to the head.

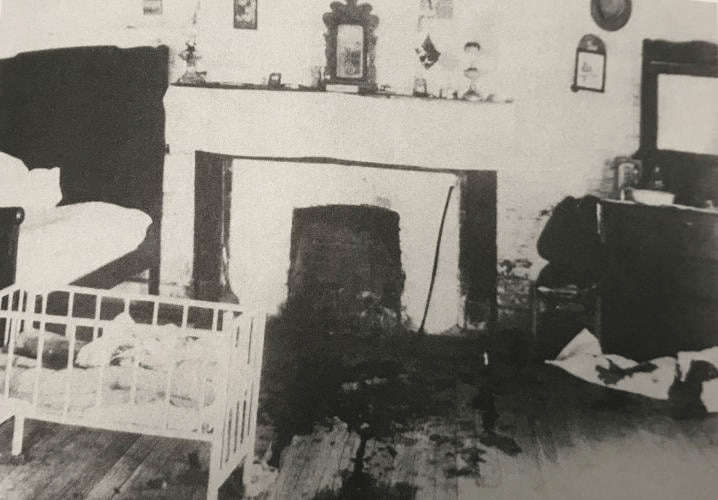

Lawson home murder scene

When relatives and neighbors later found the bodies, they noticed that Charlie had arranged them with a peculiar care. Reports say he placed the victims with their arms crossed over their chests and small pillows or folded clothing under their heads, as if in deliberate repose. This ritualistic staging deepened the sense of horror and suggested that he was not acting in a wild frenzy but with grim, organized intent.

The suicide in the woods

After killing his wife and six of his children, Charlie left the farmhouse and walked into the nearby woods with his shotgun. As the day wore on, relatives arrived at the home to wish the Lawsons a Merry Christmas and instead encountered what one newspaper described as a “shocking scene of carnage.” Word spread quickly, and neighbors organized a search for Charlie, fearing he might return or target others.

Several hours later, a gunshot rang out from the forest. Searchers followed the sound and discovered Charlie’s body on the ground, dead from a self‑inflicted shotgun wound. Marks in the soft ground showed that he had been pacing around the area, leaving a clear track in a circle or pattern near the tree where he ultimately died, suggesting he may have agonized for some time before finally pulling the trigger.

In his pockets, searchers found two short, cryptic notes. They reportedly read:

“Trouble can cause”

“No one to blame but”

The unfinished nature of the sentences has fueled endless speculation. Some interpret them as evidence that Charlie believed “trouble” (whether financial, medical, or moral) had driven him to this, yet he also claimed full responsibility: “no one to blame but [me].” Others see them as fragments of a disordered mind.

Public shock and macabre tourism

The funeral for the Lawson family drew a huge crowd, with estimates of thousands of people attending to witness the burial of Fannie and the six murdered children. They were interred together in a single grave, with baby Mary Lou reportedly placed in her mother’s arms. Charlie was buried separately, and public sentiment toward him was overwhelmingly condemnatory, mingled with morbid curiosity.

Caskets containing Lawson family victims

In a controversial move, Charlie’s brother, Marion Lawson, soon turned the family home into a roadside attraction. For several years, visitors paid admission to walk through the preserved murder scene, with the bloodstains left visible and Marie’s partially eaten Christmas cake displayed on a table. So many visitors tried to take raisins or crumbs as souvenirs that the cake eventually had to be placed under glass; later, after the house attraction ended, the cake was reportedly exhibited in carnival sideshows before a relative finally buried it.

Newspapers and word of mouth spread the story far beyond Stokes County. The combination of Christmas, a seemingly ordinary farm family, and the sheer brutality of a father annihilating his household made the case one of the most notorious Southern crimes of the early twentieth century. Over time, the Lawson murders moved from news into folklore, inspiring ballads, local legends, and true‑crime books that sought to explain the inexplicable.

Theories: head injury, madness, and incest

No clear motive was ever definitively established. Contemporary newspaper coverage often suggested that Charlie had “suddenly become insane,” reflecting the era’s tendency to invoke madness when no obvious explanation fit. Later investigators and family members added layers of possible context, but none can be proven beyond doubt.

Three major theories recur in modern discussions:

Head injury and mental deterioration

Some accounts say Charlie suffered a head injury a few months before the murders while working (for example, being struck while digging a ditch), after which he developed severe headaches, insomnia, and a marked change in personality. A doctor reportedly examined him and declared the injury minor, but relatives later described him as more irritable and volatile. An autopsy after his death found no clear structural brain abnormality, though medical techniques at the time were limited, leaving open the possibility of undetected damage. Supporters of this theory see the murders as the act of a man whose mental state collapsed due to physical trauma combined with stress.Incest and a pregnancy

The most controversial theory, popularized in Trudy J. Smith’s research and in later retellings, alleges that Charlie had impregnated his eldest daughter, Marie, and that he killed the family to cover up the incest and potential scandal.Marie reportedly confided to a close friend, Ella May Johnson, that she was pregnant and that her father was the father of the child.

Charlie’s niece, Stella Lawson, later claimed she overheard Fannie expressing concern about an “improper relationship” between Charlie and Marie.

No autopsy was performed on Marie to confirm pregnancy, and there is no official medical record supporting this claim, so the evidence remains purely testimonial and retrospective. Nonetheless, the incest theory has become widespread in books and podcasts, shaping how many people now interpret Charlie’s actions.

Financial strain and despair

Another line of thinking emphasizes the economic context: the looming Great Depression, the precarious finances of small farmers, and the crushing pressure of supporting a large family. Under this view, Charlie may have felt trapped and hopeless, seeing murder‑suicide as a twisted way to “spare” his family or escape humiliation. However, the fact that he spared his oldest son, Arthur, complicates any simple “mercy killing” narrative. Some suggest he wanted a male heir to survive to carry on the Lawson name; others speculate he feared Arthur might be strong enough to fight back if present.

It is possible that more than one of these factors played a role - mental instability, possible sexual abuse, and financial strain rather than a single, neat motive. What remains certain is that no note or statement from Charlie explicitly explains his thinking, leaving the “why” permanently unresolved.

Arthur Lawson and the later years

Arthur, the only surviving child, had been sent to town on an errand for ammunition when the killings occurred. Some see this as evidence that Charlie deliberately removed him from the house as part of a plan; others think it was coincidental or simply related to hunting. Arthur later married and had children of his own but died in a truck accident in 1945 at the age of 32. His early death added another layer of tragedy to the family’s story and cut short any full, public account he might have given of his father and the family dynamics.

The Lawson murders continued to echo through the region in the form of stories, ghost tales, and ballads. Trudy J. Smith and M. Bruce Jones’s books - first White Christmas, Bloody Christmas and later The Meaning of Our Tears - compiled oral histories, documents, and family recollections, helping to cement the case as a staple of Southern true‑crime lore. More recent podcasts and documentaries revisit the evidence and testimonies, often returning to the same unresolved questions about motive and mental state.

Ballads, folklore, and a dark legacy

Like the Stagger Lee case several decades earlier, the Lawson murders inspired musical responses. A folk ballad often titled “The Murder of the Lawson Family” or similar emerged, recounting the events in mournful verses that stress the horror of a father murdering his children on Christmas Day. Some versions frame the crime as a warning about sin and divine judgment, reflecting the strong religious culture of rural North Carolina; others linger on the pathos of the children and the bewildered community.

Over time, the Lawson farm became a kind of dark pilgrimage site, with the house attraction, the grave, and the famous portrait reinforcing the story’s grip on local imagination. The case has since been discussed alongside other Christmas‑season family annihilations as a particularly stark example of how domestic violence can shatter the sentimental ideal of the holiday.

What sets the Lawson murders apart is not just their brutality, but the sense of opacity at their core. There is no clear confession, no definitive financial or legal trigger, only a cluster of troubling hints: a head injury, whispers of incest, economic pressure, an out‑of‑character shopping trip and portrait, a carefully staged crime scene, and two unfinished sentences in a dead man’s pockets. That uncertainty has allowed the story to be retold, reinterpreted, and argued over for generations.

Nearly 100 years later, the Lawson family murders remain a chilling reminder that even in seemingly ordinary families, hidden stresses and secrets can erupt in catastrophic ways - and that some of the darkest chapters in true crime history are the ones where, for all the facts, the ultimate motive can never be fully known.

Banish bad ads for good

Google AdSense's Auto ads lets you designate ad-free zones, giving you full control over your site’s layout and ensuring a seamless experience for your visitors. You decide what matters to your users and maintain your site's aesthetic. Google AdSense helps you balance earning with user experience, making it the better way to earn.