Sal Mineo’s life reads like a compressed history of postwar Hollywood: meteoric teen stardom, a bold attempt to grow into adult roles, a struggle with typecasting and sexuality, and finally a shocking murder that has never fully lost its aura of mystery. Born to Italian‑American parents in the Bronx in 1939, Mineo rose from neighborhood kid to two‑time Oscar nominee by the age of 22, only to see his film opportunities shrink just as he was coming into his own as an adult performer and director. When he was stabbed to death outside his West Hollywood apartment in 1976, he was only 37 and on the verge of what friends believed might be a second act in his career.

Bronx Beginnings and Early Breakthrough

Salvatore Mineo Jr. was born on January 10, 1939, in New York City, the son of Sicilian‑born coffin maker Salvatore Sr. and Josephine Mineo. He grew up in a working‑class Italian‑American section of the Bronx, where his parents noticed early that he gravitated toward performing and had boundless energy, but struggled with school and discipline. A stint in a reform school for petty trouble was cut short when a social worker steered him toward acting as a constructive outlet, a redirection that changed his life.

By his early teens, Mineo was working steadily on stage. He landed small roles in Broadway and touring productions, but his big break came when he joined the cast of the original Broadway run of The King and I, playing the Crown Prince opposite Yul Brynner. The combination of theatrical discipline and his striking, expressive face made him stand out to talent scouts, and television appearances soon followed as the rapidly expanding medium searched New York stages for young actors. Hollywood took note of the boy from the Bronx, and Universal brought him west, where he transitioned quickly to feature films.

In 1955, Mineo appeared in supporting roles in Six Bridges to Cross with Tony Curtis and The Private War of Major Benson with Charlton Heston, giving him his first exposure to wide movie audiences. But it was his next film that would define his image for decades and cement his place in film history.

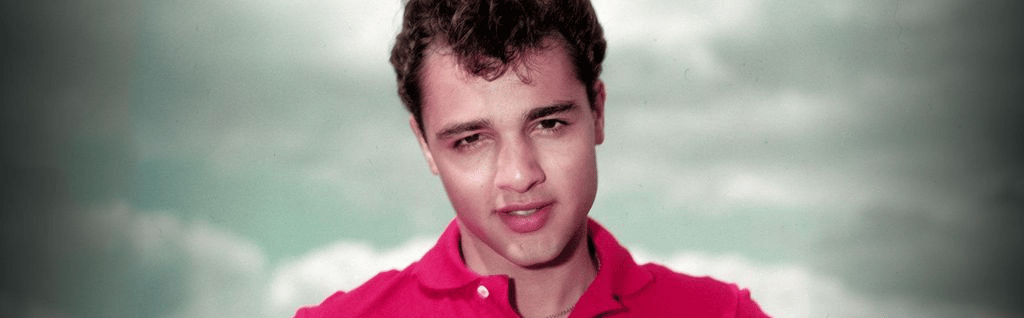

“Rebel Without a Cause” and Teen Idol Status

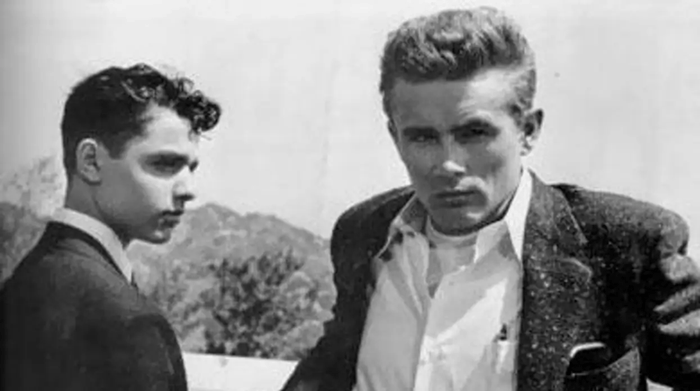

Mineo’s breakout came as John “Plato” Crawford in Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955), opposite James Dean and Natalie Wood. Plato, the fragile, emotionally starved teen who fixates on Dean’s character Jim Stark, gave Mineo an unusually complex role for a young actor; the performance suggested both vulnerable adolescent confusion and hints of queer subtext that were striking for the time. His work won him an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor at just 16, and he quickly became a teen idol, drawing fan clubs, magazine covers, and frantic studio attention.

Mineo and James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause

The mid‑ to late‑1950s were Mineo’s peak as a conventional studio star. He appeared in George Stevens’ epic Giant (1956), again alongside Dean (in one of Dean’s final film appearances), and headlined juvenile‑delinquent dramas like Dino (1957), which capitalized on his “troubled teen” persona. Publicists emphasized his dark good looks and “sensitive rebel” image, while the studios pushed him into crossover ventures: he recorded several pop singles and made television variety appearances in an effort to position him as a teen crooner as well as an actor.

The teen‑idol strategy brought attention but also boxed him in. As he moved into his twenties, Mineo found himself struggling to shed the juvenile roles that had made him famous. Hollywood in that era had a long record of discarding former child and teen stars once they aged out of their niches, and Mineo was keenly aware that he needed a serious adult part to reset his trajectory.

An Oscar for “Exodus” and a Career Crossroads

That adult role arrived with Otto Preminger’s Exodus (1960), in which Mineo played Dov Landau, a young Jewish Holocaust survivor turned Zionist fighter. The part allowed him to display intense dramatic range, moving from traumatized victim to committed militant, and he won his second Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor. He also received a Golden Globe for the performance, reinforcing the sense that he might escape the teen‑idol trap and build a long career as a serious character actor.

Yet Exodus turned out to be more of a high‑water mark than a launching pad. As the 1960s unfolded, Mineo discovered that Hollywood casting directors still saw him as either the juvenile delinquent of Rebel or a typecast ethnic outsider. He took roles in films such as The Longest Day (1962) and Cheyenne Autumn (1964), and later appeared as Dr. Milo in Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971), but the parts were often supporting and sometimes thinly written. Meanwhile, younger actors and changing fashions pushed the 1950s crop of teen idols to the margins.

Mineo’s personal life also put him at odds with the era’s norms. By the late 1960s and early 1970s he was more open within his circle about his attraction to men, and biographers have described him as gay or bisexual at a time when openness about same‑sex relationships could still be damaging to a Hollywood career. He had previously been linked romantically to female co‑stars, notably with actress Jill Haworth, but eventually built a committed relationship with actor Courtney Burr. While the new openness gave him personal stability, it did not translate into bigger roles in an industry still skittish about queer identities.

Reinvention on Stage and Behind the Scenes

As film offers dwindled, Mineo increasingly turned to theatre and television to sustain his career and exercise his creative ambitions. He directed and acted in stage productions, including End as a Man and, most notably, the provocative prison drama Fortune and Men’s Eyes, which dealt explicitly with sexuality and power behind bars. Directing and producing the play in the late 1960s and early 1970s allowed Mineo to push boundaries that mainstream film would not yet touch, and gave him respect among theatrical peers who saw his commitment to challenging material.

He also worked steadily in TV movies and guest spots on series, including appearances on Mission: Impossible, Columbo, and S.W.A.T., demonstrating his versatility and professionalism even in modest roles. Financially, though, the work was uneven, and by the mid‑1970s he was no longer living the glamorous life one might associate with a two‑time Oscar nominee. Friends and later biographers describe a period of career frustration mixed with bursts of creative energy, as he sought the right project to mark a comeback.

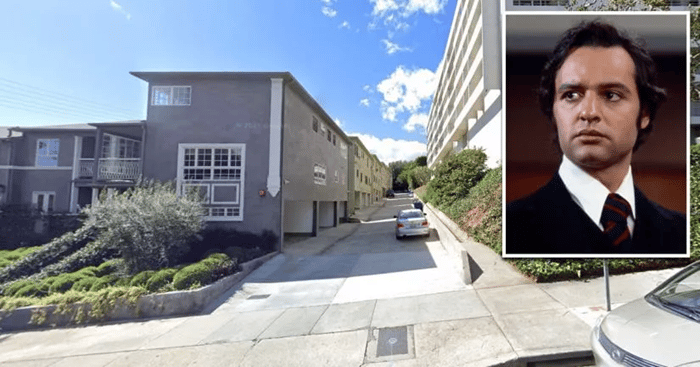

That opportunity seemed to arrive when he was cast in the play P.S. Your Cat Is Dead, a dark comedy with strong character work that was scheduled for a Los Angeles run after a San Francisco engagement. Rehearsals for the Los Angeles production brought Mineo a renewed sense of professional momentum; castmates recalled that he was excited about the role and optimistic about revitalizing his stage and screen prospects. It was during this hopeful moment that his life was abruptly cut short.

The Night of the Murder

On the evening of February 12, 1976, Mineo returned to his West Hollywood apartment on Holloway Drive after a rehearsal for P.S. Your Cat Is Dead. Accounts from neighbors and later reporting indicate that he parked his car, stepped into the alleyway leading to his building, and was suddenly attacked. Witnesses heard his cries for help and found him collapsed, bleeding from a stab wound to his chest; attempts to revive him failed, and he died at the scene at just 37 years old.

Sal Mineo’s apartment building and site of his murder

Initial assumptions by law enforcement framed the killing as a robbery gone wrong. However, early details complicated that picture: money and valuables were reportedly found on Mineo’s body, suggesting that theft had not been the main motive or that the attacker had fled quickly without taking anything. The nature of the attack - apparently a single, well‑placed stab to the heart delivered as Mineo was taking out his car keys - struck some observers as more like an ambush than a scuffle.

For months, the investigation appeared to stall. Rumors proliferated in the press and within Hollywood circles, including speculation that Mineo’s sexuality might have played a role, whether through a targeted hate crime, a pick‑up gone wrong, or extortion and blackmail scenarios linked to his private life. None of these theories were substantiated publicly at the time, and the lack of clarity fueled a sense that a cloud of mystery surrounded the case.

The Arrest and Conviction of Lionel Ray Williams

In 1977, roughly a year after the murder, police arrested Lionel Ray (“Ray Ray”) Williams, a man with a record of robberies and other offenses, in connection with Mineo’s killing. The case against Williams leaned heavily on circumstantial evidence and witness statements: among other things, investigators tied him to a small car similar to one reportedly seen near the scene and obtained testimony from acquaintances who claimed he had boasted about stabbing someone in Hollywood.

Williams was tried and convicted of second‑degree murder, with prosecutors maintaining that Mineo was the victim of a random robbery attempt that escalated into lethal violence. He received a life sentence, though he later became eligible for parole; reports indicate he was released after serving a significant portion of that term. Officially, the case was closed, with law enforcement regarding the crime as a tragic but essentially straightforward street killing.

Even at the time, however, questions lingered. Some witness descriptions had suggested a taller, light‑haired assailant, which did not match Williams’ appearance, and skeptics argued that the robbery‑gone‑wrong theory never fully squared with the presence of cash on Mineo’s body. Over the years, writers and advocates have revisited the case, contending that Williams may have been misidentified or over‑charged, and proposing alternative narratives ranging from targeted personal revenge to more exotic conspiracy theories. No court has overturned the conviction, but the controversy has kept the circumstances of Mineo’s death in the public imagination.

Legacy: A Trailblazer Remembered

Despite a relatively short career arc, Sal Mineo left a lasting mark on American film and on the representation of sensitive, troubled youth on screen. His portrayal of Plato in Rebel Without a Cause remains one of the most discussed performances in 1950s Hollywood cinema, especially for its coded depiction of queer longing and alienation at a time when such themes could not be explicitly addressed. The part, and Mineo’s work in it, helped broaden the emotional range allowed to teenage characters, pushing beyond simple delinquent stereotypes.

His role in Exodus further confirmed his abilities as an actor capable of embodying trauma, idealism, and complexity, and the two Oscar nominations he received before turning 23 testify to his early promise. Though the industry’s typecasting and prejudices limited his later opportunities, the choices he made in theatre, directing and acting in challenging plays that explored sexuality and power, show a performer striving to engage with material that resonated with his own life and times.

In the decades since his death, Mineo has become a significant figure in queer film history and in studies of Hollywood’s treatment of young stars. Biographies such as Michael Gregg Michaud’s Sal Mineo: A Biography and works like Sal Mineo: His Life, Murder, and Mystery have pieced together a fuller picture of his relationships, his struggles, and his artistic ambitions. The site of his murder in West Hollywood has been documented and memorialized by LGBTQ archives, placing his story within a broader narrative of violence and visibility surrounding gay men in the 1970s.

For fans of classic cinema, Mineo’s career can feel like a haunting “what if”: what if Hollywood had given him more room to grow beyond the teen roles of his youth, and what if, on that February night in 1976, he had reached his door a few seconds sooner. Yet even truncated, his body of work endures, a reminder of how quickly stardom can rise and how abruptly it can end - and of the talent of a Bronx kid who, for a time, illuminated some of Hollywood’s most indelible films.

One Simple Scoop For Better Health

The best healthy habits aren't complicated. AG1 Next Gen helps support gut health and fill common nutrient gaps with one daily scoop. It's one easy routine that fits into real life and keeps your health on track all day long. Start your mornings with AG1 and keep momentum on your side.