The 1926 disappearance of nationally-known Christian evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson in Los Angeles is one of the strangest crime‑adjacent mysteries of the early 20th century: a supposed drowning, a miraculous return from kidnappers, a shadowy radio engineer, a cottage on the California coast, and a grand jury that ultimately charged the famous evangelist instead of any abductors.

A Star Vanishes into the Surf

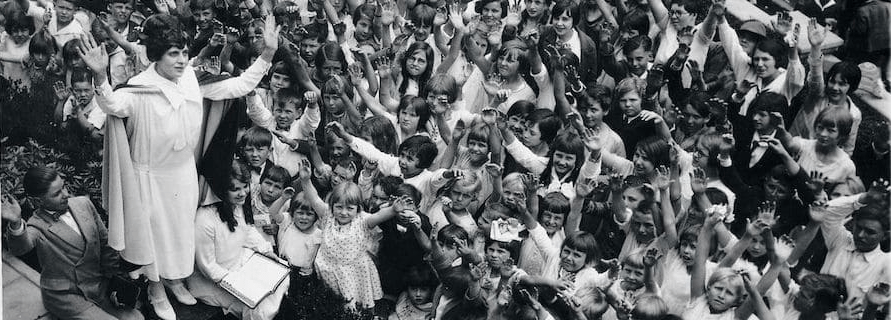

On May 18, 1926, Aimee Semple McPherson was at the height of her fame. The 35‑year‑old Pentecostal evangelist had built Angelus Temple in Los Angeles into what was effectively the city’s first modern megachurch and had become a national radio celebrity. One historical profile describes McPherson in the mid‑1920s as “the evangelist with the biggest following in the United States,” with crowds that could reach 30,000 or more at outdoor or special events.

Sister Aimee preaching to her followers’ children

That afternoon she went to Ocean Park Beach, just north of Venice, with her secretary to work on a sermon under a beach umbrella. At some point, Aimee left her chair and headed toward the water. She did not come back.

Her secretary raised the alarm, and within hours the story that “Sister Aimee” had likely drowned was front‑page news. A May 19 edition of the Los Angeles Record ran multiple banner stories announcing that “the ocean opened its arms” and took “the world’s greatest woman evangelist,” capturing the public mood of grief and morbid fascination. Searchers dragged the surf and divers combed the water; one diver reportedly died of exposure during the effort, and at least one distraught follower is said to have drowned herself in despair.

Even in those first days, the disappearance had the feel of a crime story: a famous woman gone without a body, a suspiciously blank stretch of time at the water’s edge, and rumors that she had been seen elsewhere, alive. As days turned into weeks with no corpse, Los Angeles newspapers pivoted from tragedy to speculation. Was it an accident, suicide, kidnapping, or an elaborate hoax?

The Kidnapping Story

On June 23, more than five weeks after she vanished, news broke that Aimee Semple McPherson had been found alive. She surfaced not in California but in Douglas, Arizona, just over the Mexican border. According to early accounts, a disheveled, exhausted woman appeared near town and was taken to a hospital; she identified herself as the missing evangelist and said she had escaped from kidnappers who had held her in Mexico.

McPherson’s own narrative, elaborated in statements and testimony, went roughly as follows: she had been lured toward a car at the beach under false pretenses, overpowered, and taken across the border. There, she said, her captors held her in a remote shack, bound her with strips of cloth torn from bedding, and threatened her life if she tried to escape or refused to write ransom notes. At some point, she claimed, she managed to slip her bonds and flee, walking for hours in the desert heat before reaching civilization near Douglas.

Investigators later located a rough shack near an abandoned mine about 18 miles from Douglas. Inside, they found an opened oil can whose jagged edge appeared to have been used to cut strips of ticking from a mattress, consistent with Aimee’s description of how she had been tied. For her supporters, this was proof that something like her story must have happened. For skeptics, it was suggestive but hardly decisive; a shack in the desert with cut fabric did not by itself prove a kidnapping.

What was undeniable was that Aimee’s reappearance ignited an even bigger media firestorm than her disappearance. Thousands greeted her return to Los Angeles. Yet as reporters and detectives began to probe the details of her story, the narrative took a sharp turn - from a hunt for kidnappers to investigation of the evangelist herself.

Enter the Radio Man: Kenneth Ormiston

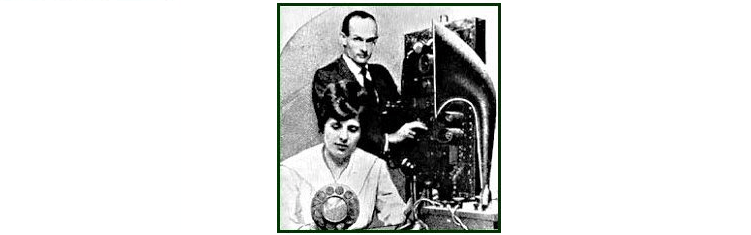

Central to the skeptical theory was Kenneth G. Ormiston, a former radio operator and engineer associated with Angelus Temple’s broadcasting work. Ormiston had left the Temple staff the year before, but his name quickly surfaced as gossip spread that McPherson might have been having an affair and had staged the kidnapping to cover a romantic disappearance.

Sister Aimee with Kenneth Ormiston

Investigators discovered that in May 1926, just days before Aimee vanished, a man resembling Ormiston had rented a small cottage in Carmel‑by‑the‑Sea, a coastal town far north of Los Angeles. Witnesses reported seeing him arrive around 3 a.m. with a woman who stayed there for about ten days. Because the timing roughly overlapped with the five‑week period when McPherson was missing, police and newspapers quickly floated the idea that the mysterious woman was Aimee herself, not a kidnapping victim in Mexico.

Ormiston was elusive at first, which fueled suspicion, but he eventually turned himself in and gave statements to authorities and the press. He admitted renting the cottage and spending time there with a woman, but insisted “Mrs. X” was not Aimee; instead, he said, she was another woman, later identified as nurse Elizabeth Tovey, with whom he was having an extramarital affair. He denounced the linking of his name with McPherson’s as “a gross insult to a noble and sincere woman” and called the press coverage “nasty publicity” and “persecution.”

In a strictly evidentiary sense, authorities never produced direct proof that McPherson had been in Carmel: there were suspicions, witness impressions of a woman with a similar build and hair color, and a trail of circumstantial details, but nothing irrefutable. Nonetheless, the cottage, and Ormiston’s presence there, became a centerpiece of the theory that the kidnapping was fiction.

Lorraine Wiseman‑Sielaff and the “Conspiracy” Theory

Another key figure who pushed the case further into crime territory was Lorraine Wiseman‑Sielaff. Initially connected to the defense side of the narrative, she later emerged as a prosecution witness, styling herself as someone who had participated in a scheme and then turned on her co‑conspirators.

Wiseman‑Sielaff claimed that elements within McPherson’s circle had concocted evidence or shaped the kidnapping story after the fact. Prosecutors hoped she could provide insider testimony that the entire abduction narrative had been scripted to cover a voluntary absence. On the strength of her assertions, District Attorney Asa Keyes convened another grand jury, this time not to pursue kidnappers but to investigate whether McPherson, her mother, and associates had fabricated evidence and lied under oath.

The shift was dramatic: what had begun as an inquiry into a potential violent crime against a famous woman had turned into a probe of whether that same woman was part of a criminal conspiracy to obstruct justice. Prosecutors floated potential charges including criminal conspiracy, perjury, and obstruction, theoretically carrying a combined sentence of up to 42 years if all counts resulted in convictions.

But Wiseman‑Sielaff proved to be a problematic witness. Over time, her statements showed inconsistencies, and defense attorneys attacked her credibility and motives. By late 1926, the prosecution came to view her as too unreliable to build a case upon. Without a strong insider witness, what remained was largely circumstantial: rumors of an affair, suspicious timing at Carmel, gaps in Aimee’s story, tantalizing but inconclusive physical traces in the desert shack.

The Grand Jury, the Trunk, and the Collapse of the Case

LA District Attorney Asa Keyes’s office pursued several phases of grand jury activity from July through the fall of 1926. The first sessions nominally focused on indicting the supposed kidnappers - faceless “Does” named Steve, Rose, and John, but no actual abductors were ever identified or arrested.

As skepticism about the abduction story grew, the focus flipped. On September 17, 1926, a judge ordered the arrest of McPherson, her mother Minnie Kennedy, Ormiston, and two others, John Doe Martin and Lorraine Wiseman‑Sielaff, on charges of conspiring to obstruct justice. At one point, investigators touted the discovery of a large blue steamer trunk purportedly linked to Ormiston and alleged to contain clothing that belonged to Aimee. A private detective, acting as a kind of go‑between for Ormiston, later called the trunk a “fake,” and that piece of “evidence” never solidified into a clear smoking gun.

The litigation churned on for months, generating tens of hundreds of pages of testimony and exhibits, making it one of the more protracted and publicity‑soaked local cases of its time. McPherson’s defense team, after initially being outmaneuvered in the press, eventually pushed back with their own narrative, emphasizing flimsy evidence, witness unreliability, and the zeal of a prosecutor who seemed determined to convict an unpopular religious celebrity in the court of public opinion.

By late December 1926 and early January 1927, the prosecution’s position had deteriorated. Lorraine Wiseman‑Sielaff’s credibility had fallen apart to the point that Keyes concluded he could no longer rely on her at trial. Without a credible insider witness and with key “discoveries” like the trunk looking dubious, the district attorney decided the conspiracy case could not be proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

Sister Aimee recovering from her ordeal

On January 10, 1927, Keyes formally asked the court to dismiss all charges against Aimee Semple McPherson, her mother, Ormiston, and the other defendants. In his filing, he acknowledged that the evidence was insufficient to sustain prosecution and remarked that McPherson would ultimately “be judged in the only court which has jurisdiction - the court of public opinion.” The legal story ended not with a trial but with a quiet collapse of the case.

Crime, Scandal, or Something in Between?

From a crime‑history perspective, McPherson’s disappearance occupies an unusual space. On paper, no kidnapping suspects were ever convicted; no fraud or conspiracy charges against McPherson were ever proven in court; and there was never a definitive judicial finding that a crime had or had not occurred. Yet the surrounding circumstances bear all the hallmarks of a 1920s media crime saga:

A high‑profile victim whose own conduct came under scrutiny

A contested narrative that shifted from victimization to alleged hoax

A web of secondary characters—Kenneth Ormiston, the unseen “Mrs. X,” Lorraine Wiseman‑Sielaff, zealous detectives, and an ambitious district attorney

Questionable evidence such as the steamer trunk and the desert shack, equally useful to both sides as suggestive but not decisive proof

The mystery of what actually happened between May 18 and June 23, 1926, has never been resolved in a way that satisfies all historians. Some biographers argue that McPherson was likely hiding with a lover and invented the kidnapping to preserve her ministry and reputation. Others point to the physical findings near Douglas, the risks she took by submitting to cross‑examination, and the lack of definitive proof of a hoax as grounds for agnosticism: the story may be embellished, but outright fabrication is not conclusively demonstrated.

What is clearer is the effect on her career. The scandal marked a turning point: while McPherson remained an important religious figure and continued to lead Angelus Temple, the aura of unassailable holiness that had surrounded her public persona was permanently dented. For Los Angeles, the case foreshadowed a pattern the city would see repeatedly in the 20th century: a celebrity scandal investigated as a crime, litigated as much in headlines as in courtrooms, and resolved less by verdict than by collective memory.

Outcome and Legacy for Crime‑History Readers

Ultimately, the McPherson disappearance is a story where the “crime” exists as allegation, suspicion, and counter‑accusation rather than a neatly solved case file. No jury ever declared whether she had been kidnapped, defrauded the public, or simply made catastrophic personal choices. The record that survives merely consists of police reports, grand jury minutes, newspaper crusades, and later reconstructions.

What can we learn from the McPherson case?

It illustrates how early 20th‑century law enforcement handled celebrity‑driven mysteries, including reliance on dubious witnesses and theatrically timed “discoveries.”

It shows how prosecutors could pivot from pursuing unknown criminals to targeting the original complainant when a story seemed too convenient.

Most of all, it captures how a supposed kidnapping in 1926 Los Angeles became a Rorschach test for the public: believers saw a persecuted evangelist battered by injustice; skeptics saw a brilliant performer caught in her own script.

Nearly a century later, the disappearance of Aimee Semple McPherson remains unsolved in the formal sense - but as a case study in media, religion, and contested crime narratives of the 1920s, it has never really closed.

Closing thought: It’s been my observation in researching this story that Sister Aimee’s appearance evolved fairly drastically a few years into her rise as a national figure. The evangelist who began as a dowdy, unremarkable brunette dressed in black transformed into a Harlowesque blonde in flowing white robes, on and off the stage - often photographed with a halo-like white circle behind her head in the background. Further, it was reported at the time that the evangelist had also undergone facial plastic surgery.

This transformation could be written off as evangelical show biz. But it could also be explained by a man, or men, in her life that she was attracted to, engaged with, and for whom she wanted to look her best.